Affiliate Disclaimer

We sometimes use affiliate links in our content. This won’t cost you anything, but it helps us to keep the site running. Thanks for your support.

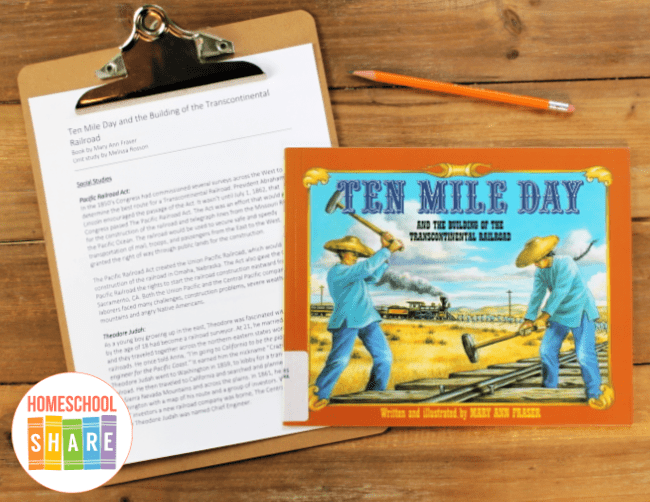

This unit study includes lessons and printables based on the book Ten Mile Day: And the Building of the Transcontinental Railroad by Mary Ann Fraser.

On May 10, 1869, the final spike in North America’s first transcontinental railroad was driven home at Promontory Summit, Utah. Illustrated with the author’s carefully researched, evocative paintings, here is a great adventure story in the history of the American West–the day Charles Crocker staked $10,000 on the crews’ ability to lay a world record ten miles of track in a single, Ten Mile Day.

Thanks to Melissa Rosson for writing the lessons and creating the lapbook for this Ten Mile Day unit study.

Ten Mile Day Unit Study Lessons

Here are some sample lessons from the Ten Mile Day: And the Building of the Transcontinental Railroad Unit Study.

Social Studies: Pacific Railroad Act

In the 1850’s Congress had commissioned several surveys across the West to determine the best route for a Transcontinental Railroad. President Abraham Lincoln encouraged the passage of the Act. It wasn’t until July 1, 1862, that Congress passed The Pacific Railroad Act. The Act was an effort that would give aid for the construction of the railroad and telegraph lines from the Missouri River to the Pacific Ocean. The railroad would be used to secure safe and speedy transportation of mail, troops, and passengers from the East to the West. It granted the right of way through public lands for the construction.

The Pacific Railroad Act created the Union Pacific Railroad, which would begin construction of the railroad in Omaha, Nebraska. The Act also gave the Central Pacific Railroad the rights to start the railroad construction eastward from Sacramento, CA. Both the Union Pacific and the Central Pacific companies and laborers faced many challenges, construction problems, severe weather, mountains and angry Native Americans.

Ten Mile Day: April 28, 1869

Charles Crocker, construction boss for the Central Pacific Railroad, heard that the Union Pacific laborers had laid 7 miles of tracks in one day. He boasted to Dr. Thomas Durant, the Vice president of the Union Pacific, that His men could lay 10 miles in a day. This exchange of boasting initiated Dr. Durant to wager $10,000 that it couldn’t be done by the laborers of the Central Pacific.

Mr. Crocker was up for the challenge and asked for volunteers from his crew. If the selected laborers were able to complete the task and lay the 10 miles in a day, they would be paid 4 times the normal wage.

At 7 a.m. the morning of April 28, 1869, Crocker and his crew of 1,400 men began laying down the tracks. It resembled an assembly line of work and by 9 a.m. 2 miles had already been completed. At the lunch break 6 miles had been completed. The laborers worked until 7 p.m. that evening. The Union Pacific surveyors were then called upon to measure the distance completed. The total was 10 miles and fifty-six feet. The Central Pacific had won the challenge and defeated the Union Pacific’s record. A total of 3,520 rails, 28,160 spikes, and 14,080 nuts and bolts were used that day to complete the job.

Social Studies: The Joining of the Rails

On May 10, 1869, in Promontory Summit, Utah, the joining of the rails was completed. It had taken many years of planning and years of laying the tracks to see it finished. The ceremony started at 11:00 a.m. with several hundred people gathered around to watch as the last rails were placed and the four spikes were driven. A crew of eight Chinese men had been selected to place the last section of rails, a symbol to honor the dedication and hard work of these laborers. People from coast to coast “heard” the last spike driven as the telegraph operator tapped “done” to the world. Both the engines, Jupiter and No.119, moved close together until they nearly touched each other on the tracks. Leland Stanford and Thomas Durant shook hands as Mr. Stanford declared, “There is henceforth but one Pacific Railroad of the United States.”

Several unusual occurrences happened the days leading up to the ceremony. Mr. Stanford had a special train prepared that would take him to the ceremony originally scheduled for May 8, 1869. In route to Promontory Summit, his train the “Antelope” was following a passenger train that was taking sightseers to the joining of the rails. As the regular train passed through a large mountain still being cleared, workmen did not notice the small green flag flying from the passenger train. The flag indicated another train was following close behind it. Immediately after the regular train passed, the workmen rolled a huge log down the side of the mountain which came to rest on the tracks. Just then Mr. Stanford’s special train came around the corner and ran into the huge log. His train engine the “Antelope” was so damaged that he had to wire the nest station to hold back the regular passenger train. Once the tracks were clear he continued on to the nest station and had his special train connected to the engine “Jupiter” who led him on to Promontory Summit.

Mr. Durant also had chosen a different locomotive then the No. 119 to take him to the Golden Spike Ceremony. While traveling to the ceremony on his special train, Mr. Durant was stopped in a small town near the Utah border. Four hundred laid off workers meet his train as it came into Piedmont, Wyoming demanding their pay. The workers had not been paid for 3 months so they chained his coach to the siding and refused to let the train continue until their wages were given to them. He was delayed for two days. It caused him great embarrassment and his original locomotive whose number is unknown lost her place in history.

While he was being delayed, the nearby Weber River had swollen and risen very high. Once Durant’s Special reached the river, the locomotive’s engineer saw the raging water and refused to cross after observing some missing bridge supports. It left the bridge unsafe to hold the heavy engine. The engineer gave the lighter passenger coaches a push that coasted them across the bridge one at a time. This left Mr. Durant without an engine. They hastily wired a message requesting a rescue. When the call came through, No. 119 was the closest engine available and became a special part in the history of the Golden Spike Ceremony.

You can grab a copy of the entire Ten Mile Day Unit Study and Lapbook in an easy-to-print file at the end of this post.

Ten Mile Day Lapbook Printables

In addition to the unit study lessons, this file also includes these mini-books for your student to create a Ten Mile Day Lapbook:

- Pacific Railroad Act Simple Fold Book

- Theodore Judah Simple Fold Book

- The Big Four Tab Book

- New Words Pocket

- The Railroad Workers Layer Book

- Samuel Morse Flap Book

- Ticket Prices Simple Fold Book

- Native American Conflicts Pull-tab Book

- Jupiter Simple Fold Book

- No. 119 Simple Fold Book

- Impact of the Railroads Accordion Book

- Utah Shutterflap Book

- And more!

How to Get Started with Your Ten Mile Day Unit Study & Lapbook

Follow these simple instructions to get started with the Ten Mile Day Unit Study:

- Buy a copy of the book, Ten Mile Day: And the Building of the Transcontinental Railroad by Mary Ann Fraser, or borrow one from your local library.

- Print the unit study.

- Choose the lessons you want to use with your student (a highlighter works great for this).

- Choose and prepare the lapbook printables you want to use with your student.

- Learn all about the transcontinental railroad.

Get Your Free Ten Mile Day Unit Study & Lapbook

Simply click on the image below to access your free Ten Mile Day Unit Study and Lapbook.